Ecology Of the City is Twenty Years Old

The phrase “ecology ofthe city” was introduced in 1997 as a simple rhetorical device to highlight the novelty of the approach to urban ecology adopted in the initial proposal for the Baltimore Ecosystem Study LTER (Pickett et al. 1997). We and our colleagues in the other urban LTER, located in Phoenix AZ, were anxious to differentiate the proposed work from the usual approach to urban ecology that had been used in the United States, and indeed most studies elsewhere, up to that time (Grimm et al. 2000).

I have been surprised that the label and its contrast with the ecology in the city has become an organizational and framing tool in many of the contemporary textbooks of urban ecology (Adler and Tanner 2013, Douglas and James 2014). However, over the intervening 20 years, the label has become more than a superficial framing strategy. It has become invested with explicit theoretical and empirical content, moving well beyond metaphor (Zhou et al. 2017). However, it may not be clear to most people that the label in fact now connotes a field of study and a mode of application. The evolution of how the idea is used also serves as an indicator of how the field of urban ecology itself has developed over that 20 year span.

The predominant approach to urban ecological research in 1997 was called ecology in the city. It is defined as a research approach focusing on biological organisms and ecological processes that are located in distinct natural, seminatural, or biologically-dominated patches within the fabric of cities, towns, suburbs, and exurbs. These habitats can be considered to be analogs of those outside of cities, whether those outside locations are rural or wild. Ecology ofthe city is defined, in contrast to ecology inthe city, as a research approach that integrates biological, social, and technological aspects (Grimm et al. 2016) of urban structures and functions, and focuses on the feedbacks among the components of urban ecosystems that represent these three aspects. The two approaches share a foundational concern with the spatial structure, heterogeneity, and functioning of urban systems ranging from single neighborhoods to urban megaregions (Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1. Urban megaregions in Asia. The ecology of the city approach applies to all urban scales. |

The two approaches can also be differentiated by the way they conceive of spatial heterogeneity, the models they use to represent spatial fluxes, and their implications for management and sustainability. Such differences have been described in more detail in an earlier post (https://baltimoreecosystemstudy.org/2017/09/24/ecology-for-the-city-also-means-with/). The contrast can also be exemplified by describing how the nine components of theory (Pickett et al. 2007) differentiate the two approaches (Table 1).

Here, I present a new diagram that may help clarify the relationship of ecology of and ecology in cities (Figure 2). Ecology in, as a focus on the biological structure and function of “green” patches in cities, is a core and ongoing interest of urban ecology. This is because such patches are widely recognized as important sources of ecosystem services in the urban landscape (Haase et al. 2014). They can also be the locus of evolutionary novelty associated with urban environments (Johnson and Munshi-South 2017). Understanding how these biologically-dominated patches are put together, what biological resources they contain, what ecological and evolutionary functions they support, what benefits and burdens to humans exist within them, or what services emanate from them, are important outcomes of research focusing on ecology in the city.

The contrasting approach of ecology of the city continues to work with biologically-dominated patches, but extends its interest to all habitat types in the urban mosaic (Table 1). Thus, it asks “what ecological and evolutionary structures and functions, environmental benefits and burdens, exist in and move among all patches in an urban area?” This inclusive focus means that ecological research under the umbrella of ecology of the city investigates patch types that may not contain obvious biological components. Ecology of the city must therefore be social-ecological research, rather than only biological research.

———————————————————————————————————–

Table 1. The components of theory (see Pickett et al. 2007) and an instance of each in the contrasting approaches of ecology inthe city and ecology of the city. The examples of each component are not complete or comprehensive. Several of the examples focus on a “filter” of concern with spatial structure as a driver of urban function. Note that “urban” or “city” here refer to the entirety of urban systems, whether investigated as a whole or not.

|

Component

|

In

|

Of

|

|

1.Domain

|

Biotically-dominated urban patches

|

Hybrid social-ecological-technological patches

|

|

2. Assumptions

|

Drawn from biology and bio-ecology

|

Additions from social-ecological science

|

|

3. Facts

|

Biodiversity, traits, genetics, population dynamics

|

Additions from social-demographic diversity, land cover and institutional attributes, information, organizational dynamics

|

|

4. Generalizations

|

Succession; disturbance; stress; natural selection; stream continuum

|

Resilience cycle; socio-economic disturbance; cultural selection; engineered stream continuum

|

|

5. Laws

|

Law of succession

|

Law of adaptive cycle

|

|

6. Models

|

Patch-corridor-matrix; Island biogeography

|

Landscape mosaic/hybrid patch dynamics; metacity model

|

|

7. Translation modes

|

Science-driven

|

Engagement-driven

|

|

8. Hypotheses

|

Patterns and mechanisms of biotic impairment

|

Adaptive capacities and limits

|

|

9. Framework

|

Nested hierarchy of key components to explain biological features and processes in “green” patches in cities

|

Nested hierarchy of key components to explain hybrid features and processes in all patches in urban mosaics

|

|

Application

|

Biological conservation

|

Sustainability planning and assessment

|

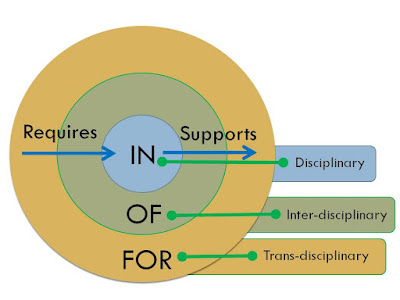

The third approach, ecology for the city, is defined as the co-production of urban research questions, and the pursuit of social ecological research intended to inform sustainable transformations in cities. This approach is discussed more fully elsewhere (Childers et al. 2015). But for this essay, the important idea is that the three approaches to ecological research about cities are not distinct from each other, but in fact interact. They can be depicted as concentric circles, with ecology in being the core, ecology of being inclusive of in, and the ecology for embracing the knowledge and approaches of the first two. Ecology in the city supports the social-ecological research exploring the ecology of the city. Similarly, work pursuant to these two approaches supports the more transdisiplinary, co-produced research of ecology for the city. Looking in the “opposite direction,” each larger circle can be considered to require the input and knowledge provided by the more focused and included domain (Figure 3).

|

| Figure 3. The conception of ecology in, of, and for as an inclusive theoretical framework, showing their relationship to the disciplinary approach each takes. |

The three approaches seen this way become nodes of interest and action in the larger field of urban ecological science. None is “the” urban ecology. Rather they are complementary and individual researchers may shift their focus and program among these approaches as time and circumstances permit or require.

The twenty years of research, education, and community engagement motivated by the first expansion of our attention in Baltimore from ecology in to ecology of the city, has continued to invite conceptual clarification. It also suggests that the empirical content of research of the entire field continues to require understanding the biology within green patches, but also requires understanding how biologically-driven processes contribute to the functioning of patches in which biology may at first seem absent. The ecology of the city points to the relevance of ecological research and knowledge throughout the city-suburban-exurban mosaic, and demands an interdisciplinary social-ecological stance toward research. Finally, the necessity and ethical requirement for effective engagement in urban ecological systems has been codified by the ecology for the city approach.

All Three approaches as defined here make up urban ecology, and together are relevant to the integration of ecological knowledge in urban decision making, ranging from the scale of households to that of entire metropolitan authorities.

Steward Pickett

Literature Cited

Adler, F. R., and C. J. Tanner. 2013. Urban Ecosystems: Ecological Principles for the Built Environment. Cambridge University Press.

Childers, D. L., M. L. Cadenasso, J. M. Grove, V. Marshall, B. McGrath, and S. T. A. Pickett. 2015. An Ecology for Cities: A Transformational Nexus of Design and Ecology to Advance Climate Change Resilience and Urban Sustainability. Sustainability 7:3774–3791.

Douglas, I., and P. James. 2014. Urban Ecology. Routledge, New York.

Grimm, N. B., E. M. Cook, R. L. Hale, and D. M. Iwaniec. 2016. A broader framing of ecosystem services in cities: Benefits and challenges of built, natural, or hybrid system function. Pages 203–212 in K. C. Seto, W. D. Solecki, and C. A. Griffith, editors. The Routledge Handbook of Urbanization and Global Environmental Change. Routledge, New York.

Grimm, N., J. M. Grove, S. T. A. Pickett, and C. Redman. 2000. Integrated Approaches to Long-Term Studies of Urban Ecological Systems. BioScience 50:571–584.

Haase, D., N. Frantzeskaki, and T. Elmqvist. 2014. Ecosystem Services in Urban Landscapes: Practical Applications and Governance Implications. Ambio 43:407–412.

Johnson, M. T. J., and J. Munshi-South. 2017. Evolution of life in urban environments. Science 358:eaam8327.

Pickett, S. T. A., W. R. B. Jr, S. E. Dalton, and T. W. Foresman. 1997. Integrated urban ecosystem research. Urban Ecosystems 1:183–184.

Pickett, S. T. A., J. Kolasa, and C. G. Jones. 2007. Ecological Understanding. Academic Press, San Diego.

Zhou, W., S. T. A. Pickett, and M. L. Cadenasso. 2017. Shifting concepts of urban spatial heterogeneity and their implications for sustainability. Landscape Ecology 32:15–30.