A special guest post by Prof. Grace S. Brush, Johns Hopkins University.

My last post discussed how the role of people in shaping the swampy systems of the Everglades had been erased. That erasure paralleled how biophysical processes had in the past been ignored in thinking about urban systems. Because Baltimore is a coastal city, it occurred to me while I was writing that post, that there were insights about the role of swamps and wetlands in the history of our city that would be worth exploring.

|

| Prof. Grace Brush |

Who better to lead us on that exploration than Professor Grace S. Brush, one of America’s leading paleoecologists — a scientist who studies past environments and the ecological networks that existed within them, usually by using fossil pollen or larger preserved parts of plants or animals? Here is her essay, reminding us of Baltimore’s important swampy heritage, and the implications for the Chesapeake Bay that result from the reduction or obliteration of those many swampy features. S.T.A.P.

THE VERY WET PRE-COLONIAL LANDSCAPE OF THE CHESAPEAKE BAY, by Prof G.S. Brush

A prevailing question today, as the historical fish harvests of the Chesapeake and other aquatic systems are greatly diminished, is “What was the land really like, when the water was clear and seafood abundant?

Pollen and seed records in dated sediment cores indicate a forested landscape 300 years ago with most herbaceous plants belonging to wetland species. Pre-colonial soils exposed along river cuts contain water lily pollen. Sedge seeds were common in the sediment. Rainfall runoff was minimal in a pervious forest floor rich in leaf litter and decomposing wood. Hence groundwater was constantly recharged, creating wet soggy ground. Seeds of submerged macrophytes in cores collected in present day tidal fresh water marshes record open water at those locations in pre-colonial time.

|

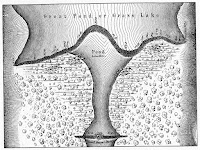

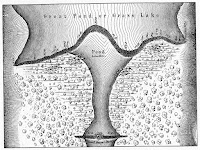

| Beaver landscape (Morgan 1867) |

Historical maps published in 1897 show springs at the mouths of many tributaries. Druid Hill Park in Baltimore City has structures built for drinking water for horses at sites where ground water surfaced. They are now dry. Upland trees such as black locust and species of oak are replacing wetland species like green ash and box elder on floodplains of many streams. This phenomenon, which we have described as a “hydrological drought” is being reported in various parts of Eastern and Midwestern USA. All through the watershed, a very large beaver population created many marshes behind the numerous dams they built on inland streams All of the evidence points to a wet environment characterized by many marshes, swamps and ponds.

|

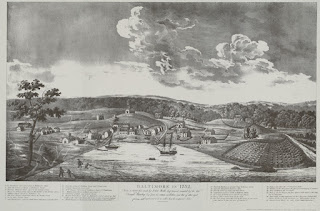

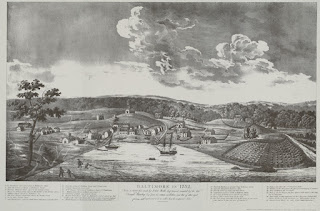

| Baltimore, 1792, with agricultural clearing. |

Within a very short time following colonization, much of the watershed was converted to agricultural land, accomplished by cutting down the trees and draining and filling in wetlands and marshes. This conversion was facilitated by the near extinction of the beaver population by the fur trade in the 18thcentury. The soil that eroded from the less pervious agricultural land — along with fertilizers — was transported by streams to estuarine waters. Excess nitrogen, a major constituent of fertilizers, is particularly harmful because of its many potential transformations in the soil and water, making it available for generations of plant growth. It can be removed from the system only by denitrification, where nitrogenous compounds are converted to elemental nitrogen and returned to the atmosphere. Denitrification occurs almost entirely in wet, anaerobic environments, such as marshes and swamps. The pre-colonial landscape, which was ideally suited for denitrification, was destroyed as nitrogen loads and sources increased.

|

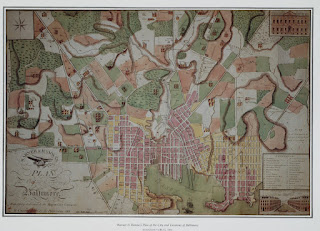

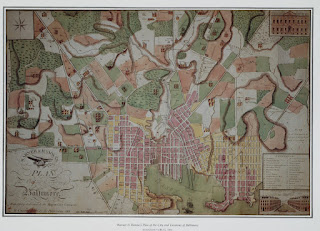

| Baltimore 1801, showing extensive, wet lowlands. |

Along with overfishing, the transformation of the landscape from wet to dry contributed directly to the fishery decrease in the Chesapeake Bay, as nitrogen not recycled to the atmosphere became a major contributor to increased eutrophication, anoxia and habitat loss in the Bay ecosystem.

Grace S. Brush, PhD, Department of Geography and Environmental Engineering, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore MD

The map of the beaver dams is from Morgan, L. H. 1867. The American beaver and his works. New York: Burt Franklin (reprinted 1970).