What Is a[n Urban] Watershed?

Watershed are urban features

| Watersheds in Baltimore |

Watersheds are important parts of both wild and civilized places. In both city and countryside, watersheds express the flow of water, with its power to connect places, its ability to accumulate and move chemicals and materials, its capacity to support rich biological activity, and its power to nourish human life. Watersheds are a fundamental part of all ecosystems and habitats.

What do watersheds do?

Watersheds are areas that collect water by surface flow and in streams, and accumulate it to the lowest spot within their boundaries. In moist climates, that spot will be a lake, wetland, or outlet to a larger stream. Urbanization alters the structure of watersheds in cities and suburbs, speeding up the rate of water flow and often depressing the biological, physical, and chemical quality of water. Because those functions of watersheds are important for the natural world, for the benefits that people draw from nature, and for people’s health, safety, and quality of life, watersheds in cities are an important, but often ignored or invisible feature of our constructed habitat.

Urban watersheds are mostly invisible now

Because streams have often been buried in pipes, encased in hard channels by steep stone or concrete walls, or hidden under streets and buildings, streams may be virtually invisible in cities and suburbs. Small streams may have been buried or rerouted due to reshaping slopes, constructing buildings, or laying out roads. Even some larger streams may have become “lost,” obscured behind factories or on the neglected fringes of parking lots, or hidden in tunnels and culverts. Without the everyday evidence of streams, city dwellers and suburbanites may be unaware of the watersheds where they live, work, and play. This means that they also do not know about the benefits and risks associated with the flows of water in their cities and suburbs.

| Baltimore City streams in 1943 (left) and 1999 (right) |

Urban watersheds are constantly modified

Even though most people may not know about their urban watersheds, the ongoing construction and reshaping of cities and suburban areas modifies urban watersheds. It is important to be aware of how urban watersheds have been modified over time by urban growth and change. Historical maps, photographs, and drawings expose the invisible watersheds of our urban areas.

Many of the alterations to urban watersheds have disconnected the natural flows of water, or have impaired the biological cleaning functions of streams and their floodplains. The hard walls of stone or concrete-lined channels disconnect the streamside soil from the moisture required to reduce pollution. The large flows of stormwater from paved surfaces and roofs erodes urban streams deep into their floodplains, stranding the floodplains high above the watertable and dries them out. These changes compromise the ability of watersheds to support plants and animals, reduce their ability to store organic matter in the soil, and impair the ability to reduce excessive levels of some urban stream pollutants. The awareness that urban and suburban watersheds experience disconnections between upstream and downstream areas, and disconnections between the streams and their banks, is key to improving the health of those watersheds and restoring the benefits they can provide to people.

Regaining awareness of urban watersheds

Urban residents and those who design and manage cities and suburbs can benefit from increased awareness of watersheds in urban areas. Awareness of urban watersheds can come from personal experience, maps of streams and the pipe networks that deliver fresh water and remove storm and waste water, depictions of the different aspects of watershed structure, and visualizations of the beneficial and hazardous flows in watersheds. It takes effort to overcome the invisibility of urban watersheds.

Once people become aware of watersheds as a part of their local sense of place, or through the need to manage and improve watershed and stream function, knowledge becomes a crucial tool. Knowledge requires data. Careful observations along a whole stream length, well documented notes of stream and watershed status, repeated photographs at set locations, and scientific measurements are all examples of knowledge following from awareness. In particular, measures of the amount of water flowing in a watershed, its biological and chemical quality, and the health of organisms that inhabit or use the streams are important contributions to knowledge about watersheds.

What does knowledge contribute to urban watersheds?

|

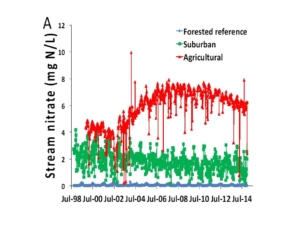

| Nitrate pollution over time in Gwynns Falls, Baltimore |

The knowledge about streams must extend through time because of ever changing conditions. It is necessary to repeat the measures so that the impact of things like drought versus wet periods, or changes in land use in the watershed, or changes in water management, can be documented. Of course, this kind of knowledge, when made available and understandable to residents and managers, becomes a stimulus for wider and deeper awareness: How is my watershed doing? Is it changing? How does it compare with other watersheds in other cities, or outside of town? Sharing knowledge in understandable terms is crucial to achieving awareness and supporting community action. Knowledge helps people to “see” urban watersheds again, appreciate the connections within them, and helps understand how they change. Knowledge promotes new levels of awareness.

How can urban watersheds be reconnected?

With the combination of awareness and knowledge, people can appreciate the potential for improving the connections in urban watersheds, and the ability of those streams and watersheds to do free, useful work for managing urban water and its benefits to environment and people. Awareness can be a tool for improving sense of place, not only along streams but also throughout entire watersheds.

What can cities, organizations, and communities do?

|

|

| Connecting neighborhoods with the Gwynns Falls. |

Biologically and socially significant actions may include the establishment of new flows to compensate for some of the disconnections city and suburban watersheds have suffered. Such reconnection can be achieved by softening the stream margins in cities and suburbs, by reconnecting communities with their watersheds and streams, and by making social flows — benefits, use, and enjoyment of urban streams and streamside habitats — more obvious and available to neighborhoods that may not now have access or social investment in their watershed.

In addition to re-connection in urban watersheds, it is important to slow the normal flow of water throughout urban areas. Increasing infiltration of water, constructing structures upstream that absorb and retain water, and reducing the amount of water used in wasteful irrigation practices are examples of slowing water flow through urban watersheds. Attention to roofs, house gutters, rain barrels, rain gardens, green roofs and other upstream interventions can contribute to slowing the flows in urban watersheds.

Recognizing that our cities and suburbs still contain watersheds and that these watersheds present many benefits and opportunities for connectivity and controlling water flow, is an important tool for design, planning, management, and social revitalization.

Box 1: Some Practical Actions for Learning About Urban Watersheds

- Map streams, pipes, and boundaries of urban watersheds.

- Map loss of original streams.

- Conduct tours along watershed length.

- Collect data on water flow and quality.

- Interpret and share watershed data with residents and decision makers.

- Focus on new designs and retrofits that slow the flow of water in urban watersheds.

- Engage residents in re-envisioning their watersheds.

- Assemble “then and now” photos and drawings of watersheds and streams.

- Promote science and art interactions focused on watersheds.

- Install are in the watersheds and along streams.

- Produce informational markers about urban watersheds.

- Involve residents in observations of streams and watersheds over seasons and years.